IDENTITY AND ONLINE WRITING

One of the digital age’s greatest changes to writing is the increased use of visual rhetoric. Our current writing technologies make it easier than ever to incorporate images and text, creating multimodal representations of writing that attempt to communicate in a more dynamic format than text on its own. The ability to easily work multi-modally has created an unprecedented explosion of mediums to work with. This means that writers must now also be designers.

But there’s a realm of visual communication that now pertains directly to personal identity. In the realm of personal communication, visuals have added a personalized, expressive element to writing that began as an informal means of adding emotion to a digital message.

- Emoticons

- Emojis

- Bitmojis

- Game avatars

- Fantasized visual representations of self

These forms have caught—

Ooh, ooh, can I narrate?

Be my guest.

The most basic level of visual communication is the emoticon. These suckers were invented by Carnegie Mellon professor Dr. Scott Fahlman in 1982. Here’s the message he sent:

THE AVATAR EFFECT

How Visual Representations of Self Affect Digital Writing

Hey Scott. Can you come back in a few minutes? We're talking about Bitmojis next. Thanks.

KNOCK KNOCK

This is the avatar I most identify myself with. She comes from a site called Poptropica.com, a Funbrain interactive website designed for ages 6-15. Her name is Shifty Shadow, a randomly-generated name I selected after scrolling through a list given to me by the website. Gameplay proceeds from a scripted narrative that allows your avatar to star in a storyline, and requires critical thinking to solve the puzzles that push the narrative forward. (Poptropica has an interesting history. It was founded by Jeff Kinney, author of the Wimpy Kid series, and has always been designed by Pearson Education as an educational game for kids. Teachers loved it and then hated it, as they were the ones who let kids play during free time in the classroom and then had problems with kids having too much fun. Because obviously, if you’re having fun you can’t be learning.)

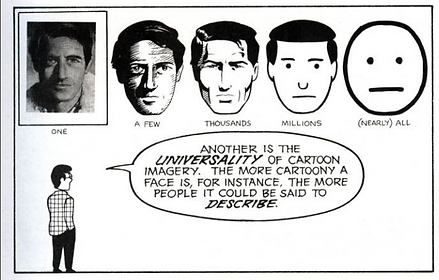

I joined when I was 12. Even though I don’t play Poptropica much anymore, I’ve kept Shadow around as both a character in personal fiction writing and as a representation of myself. I see her as a distinct character in my mind, but she’s also a mini-manifestation of my personality. I designed her physical attributes from the available ones offered during initial gameplay. I made her to look something like me, but obviously, as McCloud points out, as an animated figure she can only possess a certain degree of true likeness.

She possesses personality traits bestowed upon her during gameplay, like a snarky personality that manifests itself in the speech bubble dialogue (which is controlled by game writers, not the player). But that’s not the extent of her character. Only about half of her exists online as a pixel formation that I see as a representation of myself. The other half resides inside my brain. I’ve attributed to her certain personality characteristics that I have, as well as some I find entertaining. McCloud is right—her existence is dependent upon my identification of myself with this character, and my continued imagining her into existence.

This is a shade of identity that I rarely show to anyone, but it definitely impacts my online writing. Since I think of Shadow as a full-blown character, sometimes writing out imaginary dialogues with her can help jumpstart my writing process when I’m stuck. The dialogues usually don't appear in the finished product, but they are a vital part of the creative process. In fact, this was how I got into college and got scholarships: I wrote dialogues with Shifty Shadow to come up with feasible responses to entrance essays. An innocuous online game turned into a way of seeing myself, which in turn influenced my development as a writer.

Directly and indirectly, avatars change the way we write and the way we see ourselves. And as a result, they change the way we approach writing.

Wait what? Avatars have legal rights?

According to this, they should. You can get into some nasty stuff online, and though this article is mostly talking about physical--well, the virtual rights of the avatar's physical manifestation, it's recognizing the fact that the avatar is an extension of a real person with rights. So the avatar has rights, too.

The Shifty Shadow Effect: Examining My Own Identity in Light of My Game Avatar

And now, I’m going to break from the consideration of semi-scholarly sources to do a little introspection.

But you're right; game avatars are a way of envisioning self and existing in the digital environment, which affect how the individual interacts digitally and how they envision themselves...both of which have direct impacts on writing.

Not only that, game avatars can move back across the spectrum towards anonymity and deindividuation. Avatars are yet another mask. They're a digital representation of a person, not an actual person. The research shows that deindividuation happens frequently with avatars. People use them to dish out some harsh verbal and emotional abuse, with other avatars (and their owners) on the receiving end. Look at this!

Oh yeah, identity. Well, all this says a lot about the state of writing. For better or worse, visual forms of conveying messages are here to stay. A person's self-identity is suddenly an integral--visible--part of their online persona. It also dissolves the notion that you can keep your online and offline lives separate. Bitmojis are intended to be a way for writers (be they writers of text messages or serious blogs) to step into the digital space. We'll let Ba Blackstock have the final word on how his creations are changing the face of digital writing:

We are moving into the future where the division between your life and your digital life is going out the window; they are merging into the same thing. And in our new world, your digital representation of yourself becomes increasingly important and your ability to represent yourself and express yourself and interact with people becomes more and more important. (Blackstock)

Merging Identities: the Game Avatar

But wait! There’s even a step beyond me. I’m an avatar meant to help you communicate yourself and your emotions to your friends. But you’re not actively manipulating me; Bitmoji gives you the sets of animations with me expressing different things, and then you pick the one you think best communicates your current frame of mind and you send that one to your friends. But there’s a type of animated you that you actually psychologically become: gaming avatars.

Hmm, you're right. That's more of an identity thing than a writing thing, but it could be argued that one influences the other.

No, it's definitely a writing thing. For a start, lots of online games include a writing component. You can chat with other players and interact with their internet identities. For a lot of people, game avatars are more than just a game. They're a way of seeing themselves.

Hmm, perhaps you're right. In the article "Me, myself and I: The Role of Interactional Context on Self-presentation Through Avatars," Asimina Vasalou and Adam N. Joinson look at how people create avatars to resemble themselves and magnify certain traits to match the purpose of the avatar. Their research supports the idea that "users' communication goals are determined by the environment they enter, which in turn should impact on how they choose to present themselves via an avatar" (511). On dating sites, people tend to make their avatar more attractive. If they're on a gaming site, they design avatars that emphasize traits like "leadership, athletic ability, [and] discipline" (511). They also tend to explore different sides of their own identities, by designing avatars of the opposite gender or avatars that capture aspirational or fantasy qualities they themselves would like to possess.

Huh. So the cartoon style is effective because even though it looks like me, it's not actually me; it's you, the reader.

Yep. My voice and mannerisms are supplied by the reader's imagination. I only work if the reader interacts with me as an imaginary extension of themselves.

Cool.

How did all this pertain to digital writing again?

Let's go back to the first McCloud quote, about the simplification of the image. Simplification helps readers see the character not as someone else, but as someone they relate to.

Exactly. I’m doing this right now.

Wait, what?

Of course I am. I look a little bit like Kinsie, so I make the perfect tour guide for this journey through identity and digital writing. But I’m cartoony enough for those guys out there—at least some of you—to identity with me and my voice.

People can’t relate to you. You look too much like me.

Nuh-uh. Eryn said she was able to identify with my character.

But what about other people?

Here, I’ll prove it. Just listen to my friend Scott…

--it's a simplified version of you doing the same thing, with a focus on the concept. You don't have to spend time trying to capture the perfect expression in a snapchat, or agonize over how to write it in a text. My animated face comes off as cute and sincere, so you won't offend your friends by turning down their invitation to go out Saturday night. By simplifying your image, you're amplifying the message and the emotion you intend to convey. Simple, effective.

Plus, then I get to do cool stuff that you can't just do when you're telling a story, like this.

See? So when you pick a little image of me to send to your friends, like this one--

Yep. But let's talk about the cute part for a second. My Bitmoji represents me, but there’s also a sense in which she’s an aspirational image of me. Her hairstyle does not look like mine does most days, but what I wish it did. She doesn’t wear glasses, whereas during the school year, I’m rarely seen without them. All the same, though, when you see her making a face or doing an action, you make the connection between her and me and see me doing that same action. She’s on the realistic side of the animation spectrum, but she still works for identification.

Here, McCloud can explain this one. It's called "amplification through simplification."

Bitmoji inventor Ba Blackstock told Forbes that he created Bitmojis to fill a niche in communication that technology seems to have left behind: expressing individual identity.

Emojis have become popular in recent years because they fill a gap people didn't even know they had. They add feeling to conversation and allow you to tell if someone is being sarcastic or sweet. But as much as people love emojis and as big as they’ve gotten, they are still missing a key thing: identity. For all of human history there has always been a face to communicate with and that changes the meaning of what is said. Because Bitmoji adds that identity, it is not a fad. I believe with all my heart this is an inevitable evolution of communication. (Blackstock)

Even more than Emojis, Bitmojis are a sign of the move towards personalization. Now you can not only send a character that conveys the emotion you want to communicate--you can also send the emotion on a character that's a likeness of you, often with a word or two.

Y'all have met my Bitmoji. She looks something like me, at least enough for people to assume that I’m representing myself here.

You, but cuter!

You’re not wrong, actually. Blackstock also says that Bitmojis are supposed to be “you but cuter.” It’s part of the appeal, and what makes the representation so much fun. But don’t just take it from me, ask him:

In cartoons and animation there is a spectrum of symbolic representation. On one end you have a photo of yourself, the most realistic representation. On the other end is the smiley face, which could be anybody or everybody. It’s all about finding a balance. If you are too generic, you have no meaning. If you are too realistic, it gets creepy. There are other apps where you put your picture onto a character, and it’s like "uggh." The cartoon version of you is the cute version of you, and that’s a big part of why people love it. And maybe it doesn’t look exactly like me, but it looks enough like me that it represents me. (Blackstock)

Now doesn’t that sound familiar?

Guys, this is my Bitmoji.

They know. We’ve met.

Described on the Bitmoji website as “your own personal Emoji,” Bitmojis are the newest, most personalized form of emoticon yet. Designed by the individual user as a cartoon likeness of themselves, these little characters are meant to ultra-personalize digital writing and communication. Once downloaded, the app inserts the Bitmoji keyboard into all other writing and message-related apps, including a special icon for gmail.

With every added iOS update, it seems new emojis appear on the keyboard. The emoji library just keeps growing, giving you more ways to communicate your point via a little tiny icon of a facial expression.

Which brings us to the next step: ME!

Scott's a little excited to bring in stuff from Understanding Comics. Now where was I?

They were actually invented by Japanese designer Shigetaka Kurita, back in 1999. They got popular over in Japan, but didn’t really make it big in the U.S. until Apple added the emoji keyboard to their iOS 5 update for iPhones in 2011. In an interview with The Verge, Kurita explained the problem that led him to decide to create emojis:

In Japanese, personal letters are long and verbose, full of seasonal greetings and honorific expressions that convey the sender’s goodwill to the recipient. The shorter, more casual nature of email lead to a breakdown in communication. ‘If someone says Wakarimashita you don’t know whether it’s a kind of warm, soft “I understand” or a “yeah, I get it” kind of cool, negative feeling,’ says Kurita. ‘You don’t know what’s in the writer’s head.’

While emoticons did the trick, emojis offered the opportunity to inject fully animated little faces into your communication. One could argue that the actual appearance of the little yellow smiley-face symbol allows the recipient to identify with and read their friends into the icon.

And so the emoticon was born. They've dominated digital communication ever since, at first used mostly in emails and then text messages and then anywhere people wanted to add a little extra emotion to their text, in order to better represent their meaning. It’s often hard to read emotion into text, after all—especially with the widespread sarcasm caused by the cynicism epidemic.

Did you just reference David Foster Wallace?

Never you mind. Anyway, if you’re going to be sarcastic in a text or email, you may feel you need extra visual cues to make sure your reader understands that that’s what you’re doing. If they don’t understand that, you’re at the risk of being misunderstood. That’s why something so simple as a little representation of a smiley face, like this:

:-)

...can be a really important part of visual rhetoric. It changed the way we write in the digital age, that’s for sure.

Emojis did the same thing, but on a much larger scale. While emoticons are still in fairly frequent use, emojis are now arguably the most popular form of “emoting” in online writing.